I ended a post back on April 25 with the following question:

Does the presence of bricks-and-mortar adult entertainment establishments have a positive, negative, or no effect on the commission of sex crimes in the surrounding neighborhood?

I then asked you to consider what sort of data would be required to provide credible evidence as to what is the correct answer to that question.

Fair warning, this is going to be a longish article, but I would suggest that a credible answer to the first question above has some social value. And, full disclosure, this post is part of my ‘Studies show’ inoculation campaign.

‘Swat I do.

I do think the answer to this question is of more than passing interest.

If the presence of adult entertainment establishments (aee’s, henceforth) like strip clubs and such could be shown to reduce the incidence of sex-crimes like sexual assault and rape, this might be counted as a reason to allow them to operate. If, on the other hand, they are associated with an increase in such crimes, then that is a reason to ban them entirely. The ban/allow decision for aees is of course complex, and other factors may also be important (e.g., links to organized crime, drug use). Still, the answer could be a significant input into city policy-setting on such places.

More disclosure, this is not a very original post. I got wind of all this reading Andrew Gelman’s Statistical Inference blog back when. However, he didn’t dig into the details much. I have, and I think it is another nice illustration of an important principle: if it sounds really good, be skeptical.

Ok, then – our story begins with a paper by two economists titled “THE EFFECT OF ADULT ENTERTAINMENT ESTABLISHMENTS ON SEX CRIME: EVIDENCE FROM NEW YORK CITY”,

which was written by Riccardo Ciacci and Maria Micaela Sviatschi and published in 2021, in The Economic Journal, a well-respected outlet in my old discipline.

The following sentence from the Abstract of their paper lays out what they find –

“We find that these businesses decrease sex crime by 13% per police precinct one week after the opening, and have no effect on other types of crime. The results suggest that the reduction is mostly driven by potential sex offenders frequenting these establishments rather than committing crimes.”

Trust me, if true, that’s a big deal. A 13% reduction on average, and in the first week after the aees open.

Social scientists rarely find effects of that size attributable to any single thing. That’s huge. One might even venture to say – unbelievable.

It is not surprising that The Economic Journal was happy to give space in its pages to publish these results. And, coming back to what I wrote above, what city politician could ignore the possibility that licensing aees in their jurisdiction might reduce sex crimes by 13%?

To dig deeper we return to the ‘extra credit’ question I posed on that post of April 25 – what kind of data would one need to answer the question?

Well, you need to be able to make a comparison of sex crime numbers between areas where aees operate, and areas where they do not. An obvious possibility is to find two political jurisdictions such that one contains aees, and the other, perhaps due to different laws, does not. Then you can compare the incidence of sex crimes in those two jurisdictions and get your answer.

That approach is just fraught with difficulties, all following from the fact that the two jurisdictions are bound to be different from one another in a whole host of ways, any one of which might be the reason for any sex-crime difference you find. Demographics, incomes, legal framework, policing differences, the list goes on and on. You can try to account for all that, but it’s very difficult, you need all kinds of extra data, and you can never be certain that any difference you find can actually be attributed to the presence/absence of aees.

The alternative is to look at a single jurisdiction, like NYC, and find data on where aees operate and where they do not. Now NYC is a highly heterogeneous place – it’s huge, and its neighborhoods differ a lot, so it sort of seems like we’re back to the same problem.

However, suppose you can get data on when and where aees open and close in NYC. Then, you have before and after data for each establishment and its neighborhood. If an aee started operating in neighborhood X on June 23, 2012, you can then look at sex crime data in that area before and after the opening date. You still want to assure yourself that nothing else important in that neighborhood changed around that same time, but that seems like a doable thing.

This is pretty much what our economists did, as we will see, but there is still another issue; data on sex crimes.

All data on criminal activity carries with it certain problems. Data on arrests and convictions for crimes is generally pretty reliable, but crimes are committed all the time for which no arrests are made and/or no convictions occur. Still, the crimes occur, and for the purposes of this question, you want data on the occurrence of sex crimes, not on arrests for them.

We’ll come back to the crime data below, but I’ll start with the data on aees.

The authors note that if you are going to open a strip club in NYC there is a bureaucratic process to go through, and the first thing a potential operator of such has to do is register the business with a government bureau.

To quote directly from the paper:

“We construct a new data set on adult entertainment establishments that includes the names and addresses of the establishments, providing precise geographic information. We complement this with information on establishment registration dates from the New York Department of State and Yellow Pages, which we use to define when an establishment opened.”

So, the researchers know where each aee opened, and they know when, but do note for later, that for the ‘when’ bit they use the date of registration with the NY Department of State.

The location that they get from the Dept and the Yellow pages then allows the researchers to determine in which NYPD precinct the aee is located, and that is going to allow them to associate each aee, once it opens, with crime data from that precinct.

So, what crime data do they use? As I’ve noted, such data always has issues.

Here’s one thing the economist say about their crime data.

“The crime data include hourly information on crimes observed by the police, including sex crimes. The data set covers the period from 1 January 2004 to 29 June 2012. Since these crimes are reported by the police, it minimises the biases associated with self-reported data on sex crime.”

Ok, hold on. ‘Crimes observed by police’? What does that mean? How many of the people arrested for or even suspected of a crime by the police had that crime observed by the police? Speeders, stop-sign ignorers, perhaps? But burglars, murderers, and – the point here – sexual assault or rape? How often are those crimes observed by police?

The vast majority of crimes come to light and are investigated by police on the basis of a report by a private citizen. In the case of sex crimes, most often a victim is found somewhere or comes to the police after the crime has occurred, inducing police to begin an investigation.

This sentence from the paper clears things up….a bit.

“We categorise adult entertainment establishments by New York Police Department (NYPD) precincts to match crime data from the ‘stop-and-frisk’ program.”

Ah. You may remember NYC’s (in)famous ‘stop and frisk’ program of several years (and mayors) ago. NYPD officers would stop folks on the street and – chat them up. Ask questions of various kinds, and then fill out and turn in a card that recorded various aspects of the encounter. As we will see below, virtually none of these s-a-f encounters resulted in a report of a crime or an arrest.

So….’crime data’? From stop and frisk encounters? Need to know a lot more about how that data was used.

And we shall, but let’s go back to the other key bit of data – where and when aees opened in NYC. The date used for the aees ‘opening’ is, according to the quote above, the date on which each establishment was registered with the NY Dept of State.

Can you think of any establishment that needs a city or health or any other license to operate, that actually starts serving customers the day after it files the licensing paperwork?

To be sure, I have never operated a business, but I don’t think that can possibly be how it works. For one thing, how many different licenses do you suppose a strip club needs to operate at all? A health inspection, a liquor license, a fire inspection, building safety certificate….?

This is not a detail, because the BIG Headline this paper starts with is that a strip club reduces the number of sex crimes in the precinct in which it is located in the first week of operation. If the researchers are using the date of registration to determine when was that first week – there’s a problem.

Ok, time to let the rest of the cats out of the proverbial bag. I mentioned above that I came on this research through a post on Gelman’s blog in which some folks expressed considerable skepticism about the economists’ findings. Those skeptics are, to give credit where due:

Brandon del Pozo, PhD, MPA, MA (corresponding author); Division of General Internal Medicine, Rhode Island Hospital/The Warren Alpert Medical School

Peter Moskos, PhD; Department of Law, Police Science, and Criminal Justice Administration, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, New York

John K. Donohue, JD, MBA; Center on Policing, Rutgers University

John Hall, MPA, MS ; Crime Control Strategies, New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority Police Department

They lay out their issues with the paper in considerable detail in a paper of their own titled:

Registering a proposed business reduces police stops of innocent people? Reconsidering the effects of strip clubs on sex crimes found in Ciacci & Sviatschi’s study of New York City

which was published in Police Practice and Research, 2024-05-03.

This post is already quite long, so I am going to just give you the two most salient (in my opinion) points that are made by the skeptics in their paper.

First, as to the economists’ ‘sex crime’ data:

“The study uses New York City Police Department stop, question and frisk (SQF) report data to measure what it asserts are police-observed sex crimes, and uses changes in the frequency of the reports to assert the effect of opening an adult entertainment establishment on these sex crimes. These reports document forcible police stops of people based on less than probable cause, not crimes. Affirmatively referring to the SQF incidents included in the study as ‘sex crimes,’ which the paper does throughout (see p. 2 and p. 6, for example), is a category error. Over 94% of the analytic sample used in the study records a finding that there was insufficient cause to believe the person stopped had committed a crime….In other words, 94% of the reports are records of people who were legally innocent of the crime the police stopped them to investigate.”

And then, for the data on the openings of aees:

“This brings us back to using the date a business is registered with New York State as a proxy for its opening date, considering it provides a discrete date memorialized by a formal process between the government and a business. However, the date of registration is not an opening date, and has no predictable relationship to it, regardless of the type of business, or whether it requires the extra reviews necessary for a liquor license. New York City’s guidance to aspiring business owners reinforces the point that registration occurs well before opening.”

I close with the following. It turns out our four skeptics sent a comment to The Economic Journal laying out all their concerns about the original research, the Journal duly sent said commentary on to the authors, Ciacci and Sviatschi, and those authors responded that they did not think these concerns affected the important points in their paper. So, the journal not only did not retract the paper, it declined to publish a Commentary on its findings by the four skeptics. (Econ Journals do publish such Comments from time to time. Not this time.)

I mean, that would just make the original authors – and the Journal – look bad, no? The skeptics did, as we saw, eventually get their concerns into the public domain via a different publication – one read by pretty much nobody who reads The Economic Journal, I’m thinking.

Again – if it seems too good to be true…Objects in mirror may be smaller than they appear.

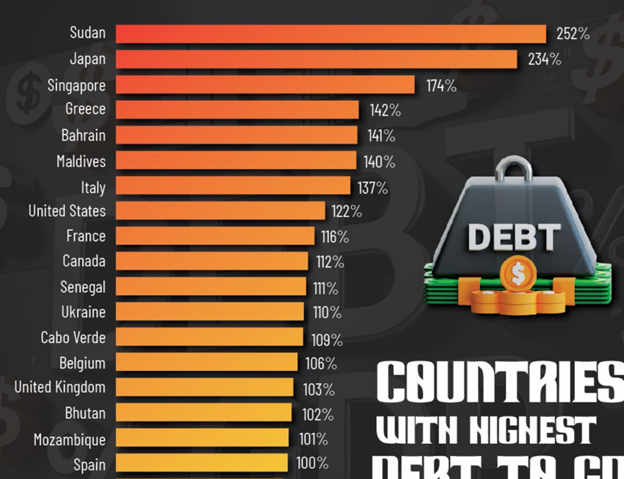

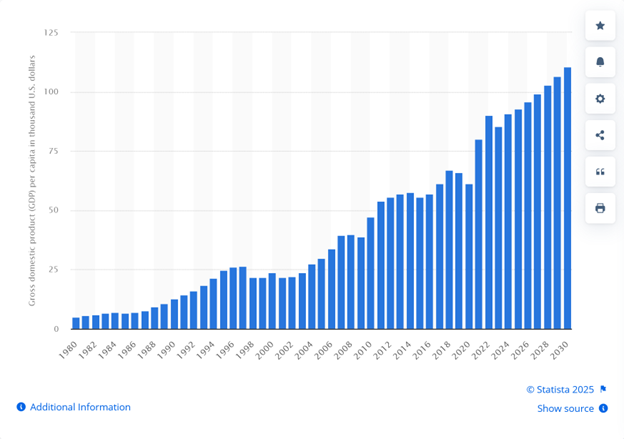

It is not at all fashionable in most Western countries these days to worry about government deficits. Government borrowing is thought to be a perfectly sensible means of providing important government programs that do good things for people. However, the above figures point out that there is one eventual consequence of this policy. Continuing deficits add to the total amount of government bonds outstanding, bonds which must be redeemed or rolled over down the road and the interest on them paid out, also using government funds. Thus, ‘servicing the public debt’ becomes a larger and larger line item in total government spending, until, as noted, one must raise increasing amounts of revenue (or further increase borrowing) in order to pay off the previous borrowing. Eventually the spending on servicing that debt can become the tail that wags the dog of government spending. It necessarily makes it harder to spend on other government programs.

It is not at all fashionable in most Western countries these days to worry about government deficits. Government borrowing is thought to be a perfectly sensible means of providing important government programs that do good things for people. However, the above figures point out that there is one eventual consequence of this policy. Continuing deficits add to the total amount of government bonds outstanding, bonds which must be redeemed or rolled over down the road and the interest on them paid out, also using government funds. Thus, ‘servicing the public debt’ becomes a larger and larger line item in total government spending, until, as noted, one must raise increasing amounts of revenue (or further increase borrowing) in order to pay off the previous borrowing. Eventually the spending on servicing that debt can become the tail that wags the dog of government spending. It necessarily makes it harder to spend on other government programs.