Tik-Tok Socialism

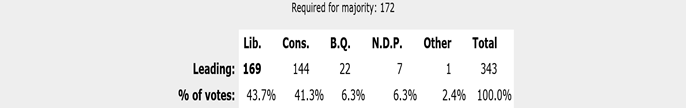

If you follow US politics at all, you will have read that one Zohran Mamdani, an Assemblyman (as they are called) in the New York State legislature, has won some 44% of the vote in the Democratic primary election for Mayor of New York City.

Now, the details are kinda complicated, so stay with me here. First, yes, this is only the Democratic primary, the winner will have to run in the general election against whoever wins the Republican primary, as well as any independents who choose to run. Eric Adams, the current sitting Mayor of NYC, has said he intends to run in that way. The phrase ‘snowball’s chance in hell’ comes to mind with regard to Mr. Adams, but that’s just me. Further, no Republican candidate has come anywhere near to winning the general election for Mayor in NYC in ages. Bloomberg was the last, although he switched to calling himself ‘unaffiliated’ by the end of his time in office.

Beyond that, you might think that 44% doesn’t sound like ‘winning’, but the Democrats have switched to using rank-order voting for their primary. What that means is that voters do not tick a box next to the name of a candidate, they instead rank all the candidates from 1 to whatever. Then a computer program first counts all the ‘1st place’ votes for all candidates. That 44% is the percentage of all first place votes that Mamdani got. The second highest total was 36%, by – wait for it – Andrew Cuomo, the former Governor of the state of New York, who stepped down from office in August of 2021, after a NY Attorney General investigation concluded he had ‘sexually harassed’ 11 women.

Back to this voting system, since no candidate won a majority of the 1st-place votes, what the computer will do is eliminate some of the candidates who got the least number of such votes (11 were running, I believe) look at the rankings of those who voted for those eliminated candidates, and add those voters’ votes to the totals of whoever they ranked second. So the remaining candidates, including Mamdani and Cuomo, will gain more votes, and this will continue until some candidate gets 50% plus 1.

So, in principle, this process could put Cuomo over the top before it does Mamdani, if most people gave their second place votes to Cuomo and few to Mamdani.

No one seems to expect that to happen, including Cuomo, who has apparently conceded that he has lost.

Now, you can read a lot about Mr. Cuomo, he’s been in politics a long time. As to the 34-year-old Mamdani, here are some things about him and the platform he ran on which I dug up easily on the great wide web.

His campaign promises include:

- Set up city-owned-and-operated grocery stores to lower the price of food.

- Institute rent-control for the vast majority of NYC’s rental properties.

- Institute a New York City personal income tax of 2% on all incomes over $1million.

- Raise the top state corporate tax rate to 11.5% (this is a state tax, I don’t see how he could do this, but it is part of his platform, which you can read here)

- Set a price of zero for riding NYC buses

- Spend $10Billion a year for 10 years to build affordable housing. (That would be more than 10% of NYC’s yearly budget)

- Raise the minimum wage in NYC to $30/hour by 2030

It is perhaps of interest that the editorial boards of both the New York Times (leftie) and New York Post (rightie) urged their readers not to vote for Mamdani.

As to his bio, his parents immigrated to the US from Uganda when he was 7. They are a Columbia University professor and an award-winning film director born in India. He went to prestigious and very expensive schools as a kid, then graduated from Bowdoin College (private, annual tuition = $86k) with a degree in African Studies. Mamdani participated in the 2024 Columbia anti-Israel encampment (no, he was not a student then). And in 2020 he posted this on his X account:

“We don’t need an investigation to know that the NYPD is racist, anti-queer & a major threat to public safety. What we need is to #DefundTheNYPD,”

So, I find myself asking a question that echoes what I asked back during the 2024 US presidential campaign – ‘Nearly 9 million people in NYC and this is what the Democrats produce as their two leading candidates for mayor?’

Cuomo vs Mandani or Trump vs Harris – which is the worse choice to be faced with?

There is a broader lesson to be learned from this, and I am hardly the first to point it out. I went to the NYC election site, and found that a total of just under 1million ballots were submitted in this primary. The City University of New York did a study of voting in NYC this year in which they concluded the following:

“The Census estimates that 5.6 million voting age citizens (CVAP) live in NYC.”

So, if only half of those were Democrats, that would say that some 38% of Democratic voters (i.e, 1million divided by 2.8million) actually voted in this primary. In fact, since the conventional wisdom is that many more than half of New Yorkers are Democrats, the actual turnout for this election is likely hovering around 30% of the Democratic voters in NYC.

If indeed then Mr. Mamdani becomes Mayor, it would be tempting to say it will happen on the basis of 46% (first-choice) support from 30-odd percent of the NYC voting age population. (That comes to about 16% of the entire voting age population in NYC, for the math-averse…)

That’s not really accurate, though. Whatever the pundits say, there still has to be a general election, and perhaps enough of the 4+million potential voters who did not vote in this primary will look at Mr Mamdani and decide it is worth their trouble to turn out and vote for someone else. Perhaps, but right now no one in NYC seems to think that is likely.

I would suggest that in any case, what happened in this Dem primary is the wider story here. It is also why the US gets the miserable and extreme candidates it does for President. Primary elections for US president in the various states in which they are held typically feature turnouts of less than 30%. If that is the percentage that turns out to vote, you can be sure it is not a 30% that is representative of the general population of Democrats or Republicans. It is fan(atic)s and true believers who show up for primaries. Indeed, one of the Trump team’s standard threats against Republican legislators who do not support his policies is to ‘primary them’. This is, to be sure, a tactic they learned from the far-left wing of the Democratic party.

When the turnout will be low in any case, the threat to swing the vote against any particular candidate by having all your fervently supportive confederates show up on election day is quite credible.

If he does become Mayor, I think it might be worthwhile to travel to Mamdani-era NYC just to see what the produce is like in the People’s Grocery Stores.

Epilogue I: Back when I taught courses in Political Economy, one topic covered every year was Voting Systems. We read about and studied Plurality Rule (i.e., first-past-the-post) versus Ranked Ballots versus Runoff Systems, etc. A standard argument from its proponents was that ranked ballots would keep extremist candidates from winning office.

Epilogue II: I have said since the emergence of Donald Trump that the Democratic Party (and most of the media’s) continuing to blame his victories on ‘misinformation’ and the ignorant, racist masses was the biggest problem faced by the USA. Someone, somewhere, needs to take a clear-eyed look at how politics in the US got to the point of offering up two candidates for President as unqualified as Trump and Harris. I have seen little sign that anyone who matters is doing that, but I will say the same about Mamdani becoming Mayor of NYC.

An article in today’s Free Press by Reihan Salam of The Manhattan Institute cites immediate post-election analysis of the NYC vote by political scientist Owen Wilson that sheds one interesting ray of light on the outcome. Wilson says that looking at precinct level data, it is striking to note that Cuomo did better in precincts with a median household income of less than $70k or more than $225k. The poor and very rich. Mamdani got more votes from the precincts with median household incomes between those two numbers. Salam characterizes those Mamdani folks as the over-educated, entitled and under-employed. They all think they should be tenured professors or financial industry mavens, and they are not. And, it is the system’s fault that they are not.

I quote here the final sentences from Salam’s article, as I really like the term ‘Tik-Tok Jacobins’.

“Just as importantly, Mamdani and candidates like him are not going away. And until sensible, sane leaders on both sides grapple with their complacency, cowardice, and pathological lack of imagination, and the way they led us here, TikTok Jacobins will keep winning—and not just in New York.”