Canadian News Updates: Unexplained, Modest, Unfair, and Smelly

I am not an Olympics follower. The website of the Globe and Mail is dominated every day now by news of the Olympics and how Canadian athletes are doing there (not so well, reading between the lines). I am happy to report that the CBC-London website as well as my local newspaper contain rather little Olympics coverage. Thank you for that.

Anyway, here is some interesting Canadian non-Olympics news from the past week.

1. But, but….

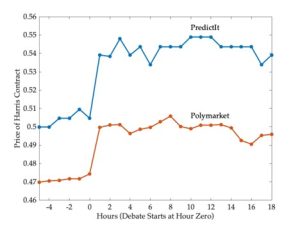

I saw a graph and a headline in the G&M today that leaves me puzzled. Still. The headline:

Alberta imports of U.S. alcohol are back, but who’s drinking it?

Under that was printed

‘In Ontario, beer, wine and alcohol from south of the border have tanked 95 per cent due to the trade war’

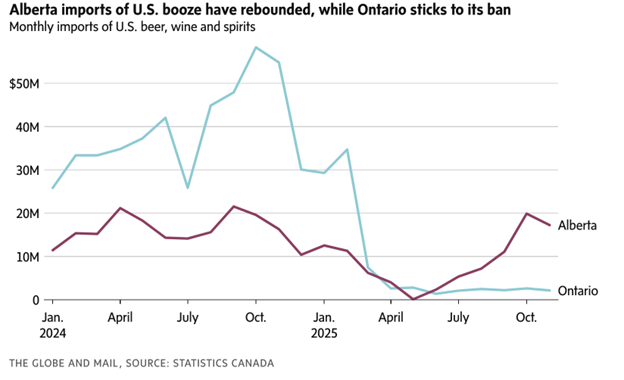

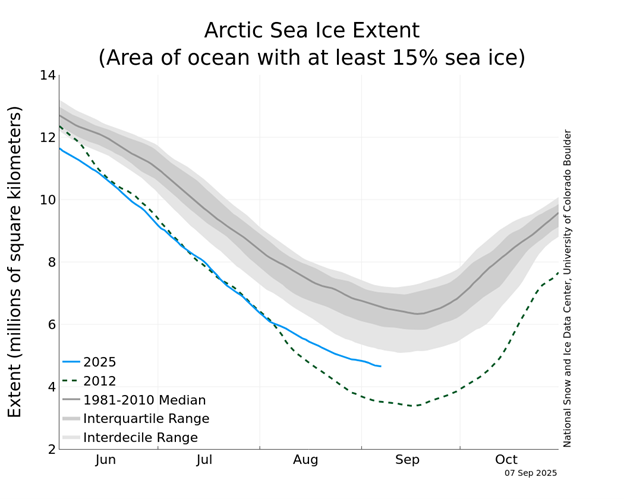

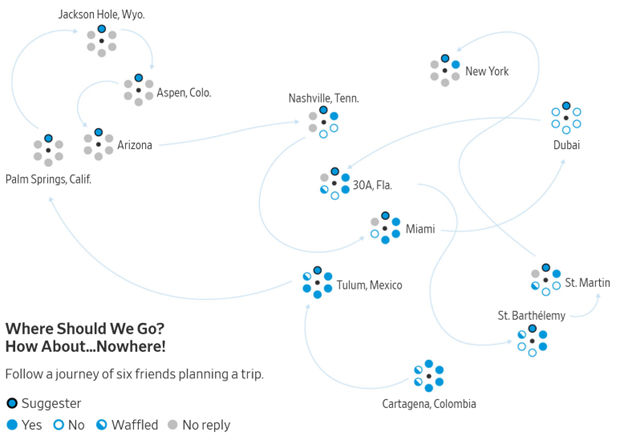

That latter assertion was backed up by this graph:

The graph as well as the quote are what puzzle me. The drop in US alcoholic beverage imports into Ontario is not due to some nebulous ‘trade war’, it is – I thought – due to the fact that the Liquor Control Board of Ontario has stopped importing all such beverages, at the order of Premier Doug Ford. This leaves me wondering – why have they only tanked 95% rather than a hundred? Is this a ban, or is it not? What is still coming in? If I am reading the graph right, more than $1m worth of US booze came into Ontario in October of ’25. Is that what travelers from the US brought in with them? I really doubt that, if you are under the customs limit, no one even tracks that.

One might expect The Globe writers to dig into this. This was, after all one of their ‘Decoder’ articles, which purports to ‘explain an important economic chart’.

The article does say this:

At the same time, Ms. Martinez said there appears to be a booming interprovincial flow of alcohol from Alberta online retailers to residents in Ontario, even though the latter restricts such shipments.

“They’re selling bourbon like crazy, and a lot of it is being shipped to Ontario, and that could explain why the volume in Alberta has gone up,” she said.

Yes, but does it explain the remaining volume going into Ontario? The amount being imported into Alberta from the US is exactly the same as it was in October of ’24, so how do we know how much is going from Alberta to Ontario? Is that, or is that not included in those numbers for Ontario? If not, where is that $1+million in US booze into Ontario coming from?

It’s the Globe, and I have learned not to expect much in the way of curiosity or effort from their reporters, so I did some research of my own. I found an online Alberta liquor store (they are not provincially run as in Ontario, that was clear right away) called BSW. I found that I could purchase online a bottle of my favourite Bourbon, Woodford Reserve, for $62.24 plus shipping. I can guess shipping would be substantial, but the shipping form I would have to fill out already had my address as being in Ontario, so I assume I could definitely do this if I was willing to pay the freight, so to speak. This bit of research does not tell us, however, whether my ordering of that bottle (or three) of bourbon would be included in the amount of US liquor imported into Ontario in February.

I know, I expect Globe articles to explain things. Silly me.

2. A modest, unfair increase

I found a story on the CBC-London website stating that after 8 years of frozen tuition in the Ontario college and university system, the province is going to allow said tuition to go up two percent a year for the next three years.

A sentence from one of the CBC articles on this:

But representatives from universities and colleges said the funding and ability to implement “modest” tuition-fee increases will ease the pressures they were facing.

It is common practice in 21st century journalism to put quote marks around single words. What does that signify? I can almost never figure it out. If the word ‘modest’ was used by someone who is being quoted, then that person should be named. My suspicion is that this is done so the media outlet can distance itself from the actual word. ‘Someone else used that word, we certainly would not.’ The CBC, being of the general editorial position that everything important should be available to all at a zero price, does not wish its readers to think that anyone at the CBC believes this tuition rise is modest.

Indeed, in another story on this increase, the quite-hopeless Prez of my former employer seems to characterize the increase as ‘modest’, so there is CBC’s plausible deniability.

Another quote from that same CBC story:

For the average yearly tuition in Ontario universities ($8,958), this could mean an average increase of $179 for the first hike. Ontario Colleges lists the average yearly cost of a diploma program at $2,400, leading to a possible increase of around $50.

I don’t understand the qualifications here. ‘could’? ‘possible’? Are those numbers equal to 2% or are they not? Perhaps the writer is just hoping that after 8 years of frozen tuition, some institutions will not raise theirs the full 2%. (If any reader or CBC reporter can name any other thing whose price has not increased over that 8 years, I will eat my hat. I own several.)

The CBC, ever on the side of the ‘little guy’, asked a couple of students what they thought of all this. Another quote:

“I don’t like that this funding had to come right out of my pocket, when as a student we already don’t have a lot of money to begin with,” said Alessia Dalimonte, a Fanshawe College student in her second-last year of studies.

No, Alessia, funding for the things we want is always better if it comes out of someone else’s pocket. And, just to be clear, the province also said it is boosting its general operating grants to universities, which does not come out of student pockets, but directly from taxpayers. Whether they or their kids went to college/university or not.

There is a photo in one story of one Taylor Timlick, described as a ‘second year student at Western University’ (that is to say, The University of Western Ontario, legally speaking) and this line:

Timleck said she finds both the tuition hikes and the changes to OSAP “unfair,” especially with the rising cost of living.

Indeed. Now that is a 21st century university student speaking, for sure. That is the word they used to describe anything they did not like – a mark, a comment on an essay, or a refusal to accept a late assignment – ‘That’s unfair, Professor’.

It is the universal adjective, one of the few concepts that has been effectively drilled into students throughout their previous 12-plus years of education.

Note its selectivity, however. Having other people – whose cost of living is surely rising – pick up most of the tab for your post-secondary education – not unfair. Everyone knows that, even the CBC.

There are other changes coming to the Ontario PSE sector, too. The Ontario Student Assistance Plan (OSAP) has for many years provided financial support to students enrolled in PSE in the province. Currently, any award from OSAP to a student can consist of at most 85% in the form of a grant with the other 15% being in the form of a loan, on which no interest accrues until the student graduates.

The province is going to alter this to a maximum of 25% in the form of a grant, with the rest being a loan. So, students who rely on OSAP will graduate with more student debt. I see this as inducing more young people to ask themselves: ‘Is this worth it?’

As my career in the PSE sector in Ontario went on, it became blindingly apparent to me that I was seeing a lot of students in my classrooms who had zero enthusiasm for university. They were there because their parents and/or their peers and/or the general zeitgeist said they should be. That’s a waste of four years, not to mention a lot of other people’s time and energy.

I would like to see a purely academic scholarship program at every university that offers a tuition grant to any student whose secondary school performance indicates they are truly brilliant. However, recognizing brilliance in the current educational environment is all but impossible, as secondary school grade inflation means tons of students have basically perfect marks. Back in the day I got such a scholarship to university, but that was on the basis mostly of a competitive exam. 21st century educators, particularly those in Ontario, just hate competitive exams, so I don’t see this happening. At least not in a way I could applaud. Such exams are, after all….oh, what is that word?……yea – unfair.

So it goes.

- Smell Test

This headline on a story on the CBC website stopped me in my tracks:

Oshawa Generals apologize after asking fans to shower before games

Really??!!

Yea, really.

I can do no more than quote from the story:

“If you went to the gym or did something that produced body odour, please shower before attending the game,” reads the email sent out by Jason Hickman, the Ontario Hockey League (OHL) team’s director of ticket sales and service.

Here is another unsurprising quote from the article:

The team issued an apology on social media on Thursday, which said, “it’s not our place to overstep like we did. We are sorry and hopefully we can wash this one off.”

Ya think? My son played hockey growing up. Every hockey parent is deeply aware of the odour that emanates from any kid’s hockey bag by halfway through a season. You do what you can to minimize it, but mostly you just learn to live with it – and keep the bag in the basement between games. Nothing a hockey spectator could generate in the way of odour can possibly compare with that.

One fan of the Generals, name of Ashley, was interviewed for the CBC story, and offered some advice:

Ashley said she hasn’t noticed bad smells at games before. She called the email a blunder for the team, saying they should have addressed odours by approaching people in person.

I would have loved to see how that ‘in person’ approach went down had the Generals tried it. A potential Monty Python sketch, for sure.

The above paragraph makes the research of Pluchino and colleagues seem like it is about real people, living ’40-year working-age lifespan(s)’, right? And, it seems that for these ‘people’ it turned out that the ‘most talented people’ were not generally the ones to achieve ‘the pinnacle of wealth’. Rather it was those people with good luck who did well.

The above paragraph makes the research of Pluchino and colleagues seem like it is about real people, living ’40-year working-age lifespan(s)’, right? And, it seems that for these ‘people’ it turned out that the ‘most talented people’ were not generally the ones to achieve ‘the pinnacle of wealth’. Rather it was those people with good luck who did well.