What Is Behind That Disturbing Graph?

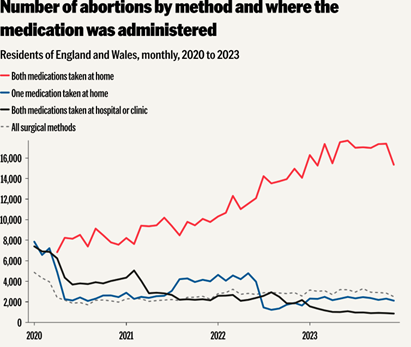

A couple of weeks back I wrote an article about Sorrye Olde England in which I stated that one of the many distressing things about the current UK was a graph showing an apparent large increase in the number of abortions in the UK over the last few years. I said then that I thought that was disturbing independent of what were one’s views on the availability of abortion.

A graph with a sharp uptake like that calls out for some digging, and Kara Kennedy, of The Free Press, which is where I first saw that graph, did some. I tip my hat to her for this. We should all be so diligent and inquisitive. She had some help, and I did a bit more digging of my own, and here is what I think I/we have been able to figure out.

First, Kennedy says she interviewed 12 British women who had abortions, and none mentioned financial difficulties as a reason for their decision to abort. She also says none of them mentioned getting any pressure to abort from anyone else. They just didn’t want to have a child.

Ok, fine, but I am not going to pretend I think we learn much from talking to 12 women in a country that is home to some 30+ million women.

Kennedy also writes this, which is more revealing:

The overwhelming majority of abortions in England and Wales in 2023—248,250 of 277,970, or 89 percent—were performed at two to nine weeks gestation. This involves taking two pills, and most of the time this can be done at home.

Apparently the number of surgical abortions then is quite small, although it too rose over the same period.

Then she writes:

Until 2020, women seeking an early-stage abortion were required to attend a clinic to take the first of the two medications under supervision.

This was changed during the pandemic, allowing women to take both pills at home, and the UK Parliament extended this in 2022.

So, most of the ‘abortions’ on that striking graph we saw in my previous post have since 2020 been women getting two abortion pills from an NHS clinic and taking them home. No one knows if they went through with taking them, whereas it would seem that a woman who took the first one in a clinic would be highly unlikely not to take the second at home.

There is therefore a real possibility that what that graph shows is more women worried about a recently revealed and early-stage pregnancy going to a clinic to get the pills, just in case. Before 2020 a woman went to a clinic to get an abortion by taking the first of two pills. Now they go to get some pills to take home, and those are two very different things. How many actual abortions occurred is very hard to say. As Kennedy writes:

Under the current system, an abortion is logged when pills are prescribed, not when—or even if—they are taken.

The graphic below from the TFP article is critical:

[I note in passing, that this graph displays monthly numbers through the end of 2023. The numbers in the previous graph that triggered all this were annual.]

Clearly, if all of those women who were prescribed the two pills took them both at home, then the upward spike in UK abortions is a real thing. But there is no way to know the extent to which that is true.

But there is still more to this. Kennedy says there has been a considerable drop in the number of UK females who use oral contraceptives. If you are brave enough to go here and work through some Excel tables, you will find she is right about that. So far as I can tell, in 2014-15 the NHS recorded some 426k females using them, whereas by 2022-23 it was only 126k. That is a huge drop, but the tables also seem to say that fewer females and males are using contraceptives at all. That may be partly demographic, as the total number using any contraceptive method fell by half over the same period. I don’t know what has happened to the total number of UK women of child-bearing age over this period, nor do I know how immigration, which has been considerable, has affected this. Still, what we have from these two pieces of info is a big rise in the number of women getting the abortion pills, while fewer are using contraception.

Kennedy says that the percentage of UK women using oral contraception as their main contraceptive method was 47 in 2013 and down to 27 in 2022. However, in 2021 the progesterone-only pill became available without a prescription, meaning the NHS has no idea how many women might now be using it.

So, guess what – it’s complicated. It seems likely that at least some of the women who obtain those two abortion pills don’t take them. They are provided free by the NHS, and having them gives one the option to abort, so why not get them if one is at all uneasy about the pregnancy? How many take the option is simply unknowable, but it seems likely to be less than 100%, meaning the spike in actual abortions is not so dramatic as the original graph suggested. Yet, at the same time, many fewer women are using contraceptive pills and (from those same Excel tables) fewer men and women are using every type of contraception, except for a small increase in the use of an ‘IU system’. I don’t know and cannot find out what that last thing is, but yes, fewer male condoms, too. (Does the NHS dispense those? Surely a guy can buy a pack at the corner store, still.) So we have a lot of abortion pills being dispensed while the overall use of contraceptives declines. Still not a happy story so far as I can see.

If the decline in contraceptive use is largely due to a decline in the size of the age group for who it is relevant, then it is even more alarming that so many abortion pills are being prescribed.

Finally, if I believed that all these women are aborting purely because they don’t think they should or are fit to have kids, as the women Kennedy talked to seem to say, well – I find that disturbing, too. These were not teenagers she spoke to.

I intend to see if I can find similar numbers for Canada and the US. I’m curious to see if similar trends are occurring there. Stay tuned.