Disability, Inc.

‘You don’t ask a barber whether you need a haircut’.

I have no idea from where or who that bit of wisdom comes, but I also have no doubt of its wisdom.

A story in the Dec 27 Globe and Mail is titled ‘As demand for disability accommodations in universities grows, professors contend with how to handle students’ requests’

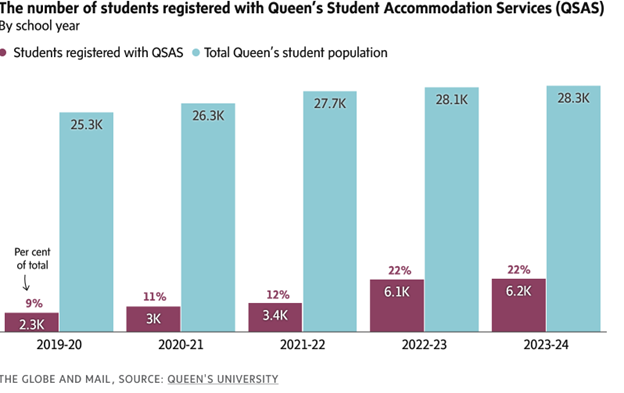

Not far into the piece one sees the graph which I have reproduced below:

A more than two-fold increase in the percentage of individuals in any sub-category of any population is notable. When something changes that dramatically there is something going on. Maybe more than one thing, but something, almost surely.

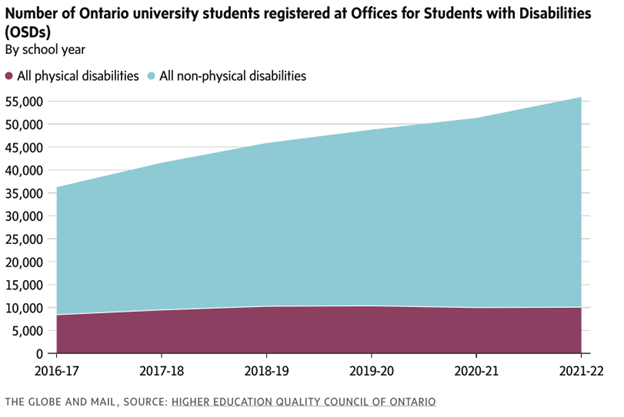

An important aspect of the phenomenon is depicted in the following graph, also from the article:

It is clear that the number of students with physical disabilities has not changed much over the depicted 5-year period, as the purple region’s upper boundary is nearly flat. However, the number of students registered with non-physical disabilities has increased by some 20,000 over the same period. Non-physical disabilities refer to things like test-taking anxiety, ADHD, difficulty with concentration, etc.

It is thus unavoidable that the source of the steep increase in students with registered disabilities is to be found in the source of the steep increase in non-physical disabilities. Importantly, these disabilities are not objectively verifiable. If a student claims to be blind or deaf or unable to walk, this can be verified by a doctor. More pointedly, if a test (like the PSA, for example) is used to diagnose prostate cancer, it is possible to determine how accurate the PSA test is. That is, it is possible to determine what percentage of false positives and false negatives arise in any population in which the test is used diagnostically. That is because surgeries and autopsies of individuals who are diagnosed in this way can determine whether they actually had prostate cancer.

There is no analog to surgery for test-taking anxiety or ADHD. There are tests, of a sort, and questionnaires, and criteria, for sure, but all of these have been developed by the ‘experts’ who are doing the diagnosis, and again – there is no way to objectively verify their results. One has ADHD if an expert on ADHD – whoever that may be – says so. That expert perhaps went through some process in determining that diagnosis but there is no device outside that ring of experts which can tell us how accurate are their diagnoses of ADHD. Determining ‘accuracy’ is impossible without the ability to determine what is true in a way that does not depend on who is doing the determining.

You can go to this link to get, for example, a pdf containing the DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for ADHD in children. You will find it a series of statements about observed behavior, such as ‘Lacks ability to complete schoolwork and other assignments or to follow instructions’ and ‘Incapable of staying seated in class’. The reality is that none of these observations are actually likely to be done by the ‘expert’, but come from the expert interviewing the parents and perhaps a teacher or two. The point is that this set of ‘criteria’ is all there is. An MD or psychologist talks to the parents and/or teachers, maybe the kid for a bit, consults this checklist, and then ‘decides’ ADHD, yes or no. One can go to another expert then, who might or might not agree, but one cannot get verification. It is not possible.

It is known, for example, that the PSA test produces ‘false positives’ at a high rate. This results in urologists generally requiring more evidence than a high PSA test value before they do anything invasive to a guy whose test showed such a high value. There is no way to talk about a ‘false positive rate’ for an ADHD diagnosis. Different experts might do the interviews, go through the checklist, then come to different answers, but there is no such thing as a ‘false positive’. If some expert says you have ADHD, the law and the university treat that as a certainty.

In my latter teaching career, when the explosion in disability exemptions among students was well underway, I was told that most university students with a disability diagnosis went into their first year with it already in place from their high school, if not earlier. The universities just carried on with accommodating them. The ‘advisors’ at Queens mentioned in the article don’t diagnose these conditions, they just decree what accommodation the student must be given for having them.

The psychology and psychiatric professions have been devoted to expanding the range of disabilities for decades now. Pretty much every kind of behavior has been given a spot as a ‘disorder’ in the DSM, including ‘oppositional defiant disorder’. Type that into google and see what comes up. I’m not an expert, but I’m quite sure I suffered from a bout of it at one point in high school.

These are barbers setting the rules for when someone must get a haircut. To be sure, not all members of all health care professions buy into the medicalization and amelioration of life. There is a reader comment at the end of the GM article from a health care worker who notes that when she pushed back against providing a ‘sick note’ for a student, the parent threatened to report her to her professional college.

Professional colleges in ‘regulated professions’ have become great agents for the enforcement of conformity. And the counsellors who set the accommodations for these diagnostic students, cannot be argued with, either. Certainly not by the likes of lowly faculty. It is worth noting that there is no science whatever behind the ‘accommodation’ business. That is to say, there are no scientific studies of the effects of giving vs not giving various ‘accommodations’ to students with registered disabilities. The standard two accommodations given are to allow more time to complete things, or to take tests in an environment separate from other students. Note that these are things that would likely allow any student to get a higher mark.

So, the disability accommodation system in Canadian education has become a system in which professionals with an interest in seeing disabilities and accommodations grow are in a position to help it do so, and in which the accommodations are such that every student would find them beneficial.

I would timidly suggest we may have found a cause for the pattern shown in the second figure above.

Predictably, this Globe article generated plenty of outrage in the comments sections, as well as some suggestions for what would or should happen now. I will close by dealing with a few of these.

- Universities should indicate on degree certificates or transcripts when a student has received accommodation in earning their credential. That’s a non-starter under both privacy and discrimination law. That it would improve the information available to society is quite beside the point, this cannot be done under current law, even if universities were willing.

- These accommodated students will be unable to compete or hold a job once they get out into the real work world. I fear this is false. The various Disabilities Acts in federal and provincial law – not to mention the Canadian Charter – pretty much insist that accommodation be given once someone is expertly diagnosed. I expect this will apply no less to workplaces than it does to educational institutions, so those accommodated students are likely to move into the workforce and insist on – and receive – similar special treatment from their employers. It is likely just a matter of time before most firms of any size have ‘disability counsellors’, just as they have HR and DEI people now.

- Once people start dying on operating tables and bridges start falling down, society will see that these accommodations are granting credentials to incompetent people and this will have to stop. This point is also often made with regard to DEI (now EDIDA at my old employer – guess what that stands for, gwan) policies, as well.

I actually think there is something to this, as some very undeserving and – honestly, ignorant – people have been receiving both high marks and degrees at my former place of employment for some time, and I have no problem believing their general ignorance, coupled with a sense of entitlement, will have costs down the road. Costs to others, I mean.

But neither the existence of EDIDA nor of disability accommodation means that all university graduates are ignorant and entitled; only that too many are. After all, universities have always given credentials to some who were undeserving. However, it is likely to take a loooong time for the impact of that increase in the undeserving to be visible out in the world, and an even longer time for it to be sufficiently obvious to enough people that the will to do something about it takes hold in society in general.

I would not hold my breath. Actually, I won’t be able to, as I expect to be long gone before it happens.

Mark Beuerman

My wife has a contractor at her work that has “ADHD”. It seems to be an excuse for incompetence.